I just visited the Houses of Tomorrow: Solar Homes from Keck to Today exhibit at the Elmhurst Art Museum. Throughout my 3 years of graduate architecture school, I never heard of George Fred Keck, nor his brother, William. Maybe I just didn’t listen closely enough, but I think I was a pretty good student (hi mom). But anyway, I get excited any time I get to learn about a new architect, so it was a fun!

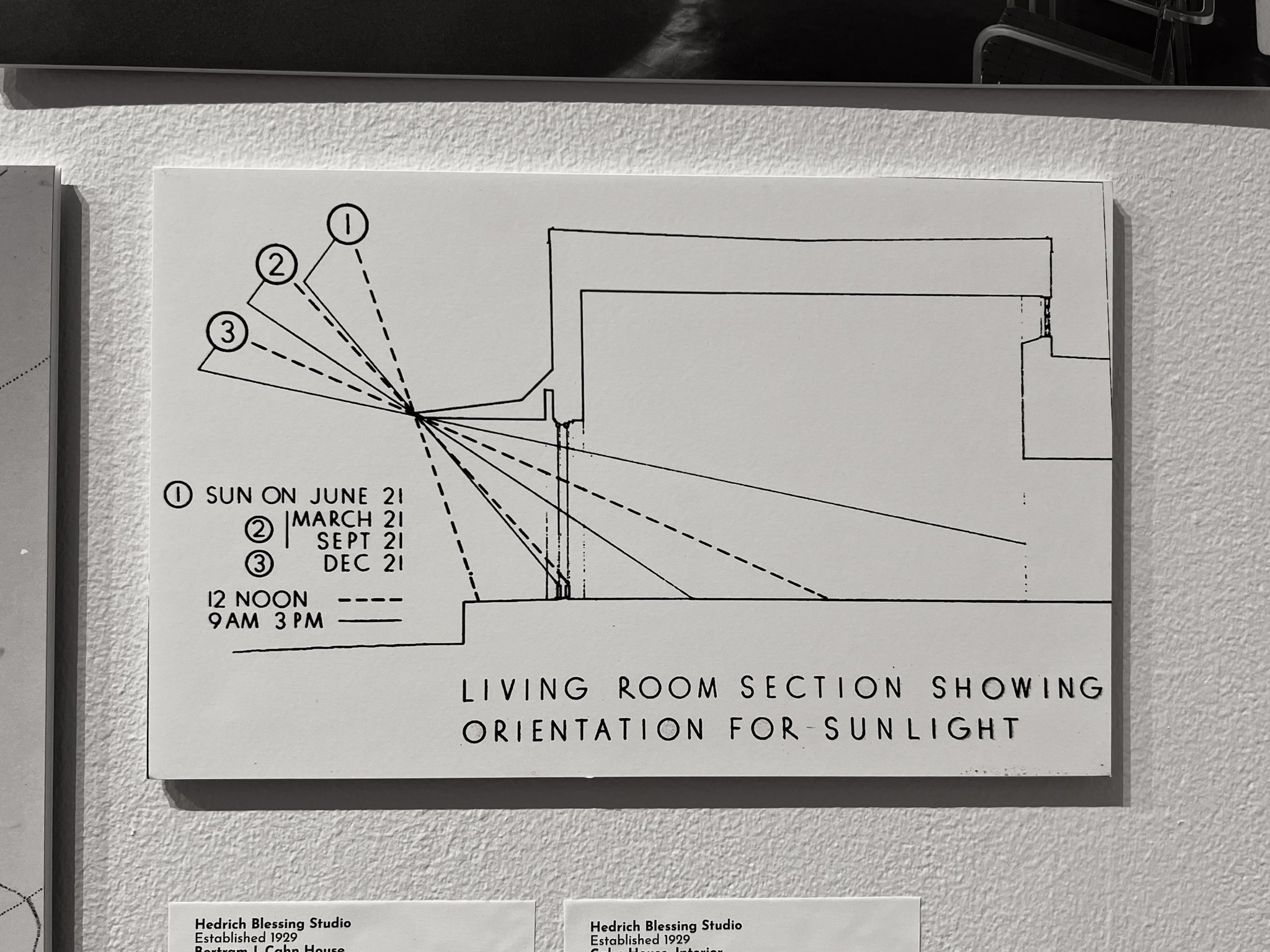

The Keck brothers were ahead of their time in technology. They are known as the first “solar architects,” harnessing the power of the sun to help passively condition indoor spaces. The principle is simple, but the execution is hard. The idea is that you want to let the sun inside during the colder months (to heat up the space) and keep the sun outside during the hotter months (make it easier on your cooling system - air conditioning or natural ventilation).

Passive Solar Orientation

Photo by Curt MacIver, Taken at Elmhurst Art Museum, Artist Unknown

The Keck brothers showed off their innovative, all-glass House of Tomorrow at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. It was a huge hit. The design was radical, and the new technology excited everyone for the amenable and luxurious domestic life to come. Initially, the attached garage was a hangar for a private airplane!

(The house was eventually moved to the Indiana lakeshore, where it is currently seeking a buyer to finance a multi-million dollar renovation plan in exchange for a 50-year lease. Anyone interested? Get it while it’s hot! Sorry, solar AND housing market joke in one.)

The second half of the gallery looked at the many private homes that the Keck brothers designed throughout their career. Mostly mid-century in style, they marketed their utility-bill-saving homes as both a financial and cultural investment. One of their larger homes was crescent shape (following the path of the sun), with the driveway running along side the interior curve. The scale and approach looked as though it could be a two-star hotel. But, most of the other homes were really beautiful - well-proportioned with nice outdoor space and fun brise-soleils.

George Fred Keck’s Crystal House was a different exploration. Its exposed exterior steel trusses no doubt influenced the future generation of high-tech architecture.

George Fred Keck's Crystal Home

Photo by Curt MacIver, Taken at Elmhurst Art Museum, Courtesy of Hedrich Blessing Studio

The curators speculate on how Keck also influenced his contemporaries. The exhibit explicitly pointed out parallels between George Fred Keck and Frank Lloyd Wright - the first being that they both have three names. No, but, FLW would eventually also design a crescent-shaped house - semi-similar in plan and function.

The exhibit remarks on emerging technologies (solar panels, high-performance windows, geothermal heat pumps, energy recovery ventilators, etc.) and current programs (LEED, PHIUS) that help the built environment limit its impact on the environment. It really is an exciting time to be a designer. It’s a challenging time but exciting time. There are so many tools and resources at your disposal.

The funny thing about the exhibit is that part of the associated art installation by Jan Tichy is housed in the adjacent building of the museum, which is Mies van der Rohe’s 1952 McCormick House. As I learned while studying in Crown Hall for multiples years, Mies’s design philosophy prioritizes design aesthetic and function, not (thermal) comfort. This discussion is worthy of an entire book, but it was an interesting - unintentionally entertaining - contrast to the museum’s exhibit.

This was my first visit to the museum, and I was pleasantly surprised. The building is really pretty, and the exhibit was well curated. It’s sad to see that these passive energy approaches have been around for almost 100 years in contemporary buildings, and they still don’t seem to be widely used. Why are net-zero energy buildings so sexy? Shouldn’t they be the status quo? Hopefully soon.